Artist Statement

Boy

Portrait of a Young Woman

Solitary Boat Beneath a Bridge

Mangia Libro

Eden

A Hundred Years

Seated Musician IX

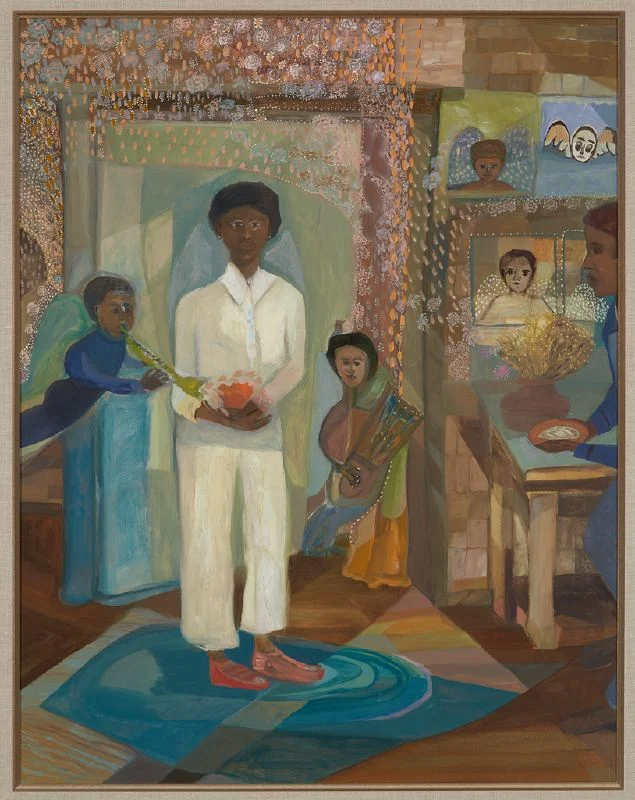

Annunciation

Ficre Ghebreyesus wrote this statement in 2000, for his application for admission to the Yale School of Art. It offers his account of how he came to painting and what it meant to him at the time.

I started painting ten years ago, but I suspect I have been metaphorically doing so all my life. When I started painting, I just did it. I had never felt a stronger urge. The pieces that flowed out of me were very painful and direct. They had to do with the suffering, persecution, and subsequent psychological dilemmas I endured before and after becoming a young refugee from the Independence War (1961-1991) in my natal home of Eritrea, East Africa. Painting was the miracle, the final act of defiance through which I exorcised the pain and reclaimed my sense of place, my moral compass, and my love for life. From Eritrea I found myself in New York City, where my tiny kitchen table instantly became the studio table.

Storytelling comes naturally in Eastern Africa, where the mainstay of culture is orally transmitted from generation to generation. Many Eritreans are still illiterate, and the culture of visual communication is relegated to Coptic Orthodox church facades and interiors. Murals and mosaics of saints and angels abound. There is an equally strong presence of Islamic iconography on the exteriors and interiors of mosques. Concomitant to these two ancient presences in my growing up years in the capital city of Asmara were war-time, mural-sized portraits of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin, and --depending if he was in favor -- Chairman Mao, as well as the Ethiopian dictator Colonel Mengistu Hailemariam.

Asmara is a beautiful city at eight thousand feet above sea-level, planned and designed by Italian colonialists at the turn of the century. In addition to the collision of architectures, iconographies, and propaganda art there was the unique, and palpable visual aesthetic of death: Soviet tanks rumbled through the streets, fighter planes strafed the skies, and deadly uniformed soldiers rummaged through the streets. It was a medieval vision of hell incarnate. Government-sponsored death squads had “powers of emergency” over any Eritrean citizen. I suspect I have carried this angst and fear of imminent explosion within me to this day, for when I paint I am accompanied by dissonances, syncopations, and the ultimate will for life and moral order of goodness.

A trip to the market guaranteed a dazzling range of traditional crafts repeated from one generation to the next without ongoing critical intervention and independent of religious function. These crafts included a dazzling range of works such as reed baskets and hand-spun, hand-woven embroidered cotton garments in exquisitely-resolved colors. The caves near my mother’s village are full of prehistoric rock drawings and paintings. My eyes took in all of this; my painting allowed me finally to process the seemingly dissonant visual information.

The painter as an individual, however, without church or mosque affiliation, and sanctioned by civilians and government is a relatively new concept for us in Eritrea, forty years old at most. When I paint in my studio in New Haven, some five thousand miles away from home, I still find myself reacting to this reality. My normative experience is inescapably Eritrean. And as it turned out for me, I also have to respond and account for the stimuli and influencing forces that I find myself open or vulnerable to, because of my life here. So far I have been able to cull the various forces such as Be-Bop, Modern Jazz(especially Thelonius Monk and Charles Mingus), polyrhythms of the African diaspora, and the great many paintings that I spend time viewing in museums, when I can take time off. I am continually recontextualizing my normative experiences in early Eritrea, and one of those manifestations has been my work as a chef, where I have found myself integrating cross-cultures into dishes. I have become a conscious synchretizer. My cooking is how I make my living, but I have also been able to make a creative experience that in fact complements my painting philosophy. As a visual artist, I can say I have reached a level that is satisfactory for an autodidact, but I realize I need more. Participating in an educational and creative process at Yale will lend me a unique chance to partake, interact, and be part of a stimulating intellectual forum.

What are dreams if one is not able to dedicate ones life to them and share them with a larger community than the self? I have few and focussed dreams in life. For one, I want to be a very good painter, and I know that will come with time and commitment. And secondly I want to open a school of the arts for financially disadvantaged children in Eritrea. This school shall act as the lighthouse that will unearth and empower the many Eritrean/African Giottos to come. Of the few painters that currently live and work in postwar Eritrea, most are relegated to didactic renderings of social/realist views of the painterly praxis, and inasmuch they have not done much to instigate critical participation from viewers by speaking for themselves, instead they keep speaking about a pre-supposed community with pre-supposed needs and solutions. In the light of such a backdrop my dream school will be about self-exploration and expression. I believe in it will be found great seeds for healing and peace. In order to carry out this dream, and my dream of becoming a much better painter, it is time for me to study in an environment where I can also soak up the resources of the University at large. It is time, at last, for me to dedicate myself to painting, to distill this lifetime of visual and emotional experience, and to learn how to live up to my potential as a painter and better share my particular vision with others.